Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the ideas, people and events that have shaped our world.

Similar Podcasts

Crímenes. El musical

En la prensa de la España del XIX, los crímenes fueron un hit. Les gustaban tanto como hoy nos gusta el True Crime. A la vez fue asentándose la ciencia forense. En esta serie relatamos algunos de los crímenes más famosos de entonces, con mucha música y algunos coros. Y entrevistamos a una criminóloga y a científicos forenses de varias disciplinas: medicina, psicología, antropología, lingüística, biología...Suscríbete a nuestra newsletter y déjanos una propinilla aquí

Internet History Podcast

A History of the Internet Era from Netscape to the iPad Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

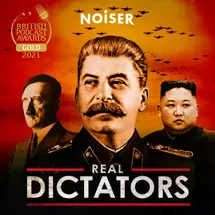

Real Dictators

Real Dictators is the award-winning podcast that explores the hidden lives of history's tyrants. Hosted by Paul McGann, with contributions from eyewitnesses and expert historians.

New episodes available a week early for Noiser+ subscribers. You'll also get ad-free listening, early access and exclusive content on shows across the Noiser podcast network. Click the subscription banner at the top of the feed to get started or head to noiser.com/subscriptions

For advertising enquiries, email info@adelicious.fm

Anarchism

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss Anarchism and why its political ideas became synonymous with chaos and disorder. Pierre Joseph Proudhon famously declared “property is theft”. And perhaps more surprisingly that “Anarchy is order”. Speaking in 1840, he was the first self-proclaimed anarchist. Anarchy comes from the Greek word “anarchos”, meaning “without rulers”, and the movement draws on the ideas of philosophers like William Godwin and John Locke. It is also prominent in Taoism, Buddhism and other religions. In Christianity, for example, St Paul said there is no authority except God. The anarchist rejection of a ruling class inspired communist thinkers too. Peter Kropotkin, a Russian prince and leading anarcho-communist, led this rousing cry in 1897: “Either the State for ever, crushing individual and local life... Or the destruction of States and new life starting again.. on the principles of the lively initiative of the individual and groups and that of free agreement. The choice lies with you!” In the Spanish Civil War, anarchists embarked on the largest experiment to date in organising society along anarchist principles. Although it ultimately failed, it was not without successes along the way.So why has anarchism become synonymous with chaos and disorder? What factors came together to make the 19th century and early 20th century the high point for its ideas? How has its philosophy influenced other movements from The Diggers and Ranters to communism, feminism and eco-warriors?With John Keane, Professor of Politics at Westminster University; Ruth Kinna, Senior Lecturer in Politics at Loughborough University; Peter Marshall, philosopher and historian.

The Speed of Light

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the speed of light. Scientists and thinkers have been fascinated with the speed of light for millennia. Aristotle wrongly contended that the speed of light was infinite, but it was the 17th Century before serious attempts were made to measure its actual velocity – we now know that it’s 186,000 miles per second. Then in 1905 Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity predicted that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light. This then has dramatic effects on the nature of space and time. It’s been thought the speed of light is a constant in Nature, a kind of cosmic speed limit, now the scientists aren’t so sure. With John Barrow, Professor of Mathematical Sciences and Gresham Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge University; Iwan Morus, Senior Lecturer in the History of Science at The University of Wales, Aberystwyth; Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Visiting Professor of Astrophysics at Oxford University.

Altruism

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss altruism. The term altruism was coined by the 19th century sociologist Auguste Comte and is derived from the Latin “alteri” or "the others”. It describes an unselfish attention to the needs of others. Comte declared that man had a moral duty to “serve humanity, whose we are entirely.” The idea of altruism is central to the main religions: Jesus declared “you shall love your neighbour as yourself” and Mohammed said “none of you truly believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself”. Buddhism too advocates “seeking for others the happiness one desires for oneself.”Philosophers throughout time have debated whether such benevolence towards others is rooted in our natural inclinations or is a virtue we must impose on our nature through duty, religious or otherwise. Then in 1859 Darwin’s ideas about competition and natural selection exploded onto the scene. His theories outlined in the Origin of Species painted a world “red in tooth and claw” as every organism struggles for ascendancy.So how does this square with altruism? If both mankind and the natural world are selfishly seeking to promote their own survival and advancement, how can we explain being kind to others, sometimes at our own expense? How have philosophical ideas about altruism responded to evolutionary theory? And paradoxically, is it possible that altruism can, in fact, be selfish?With Miranda Fricker, Senior Lecturer in the School of Philosophy at Birkbeck, University of London; Richard Dawkins, evolutionary biologist and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University; John Dupré, Professor of Philosophy of Science at Exeter University and director of Egenis, the ESRC Centre for Genomics in Society.

The Peasants’ Revolt

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the Gentleman?" these are the opening words of a rousing sermon, said to be by John Ball, which fires a broadside at the deeply hierarchical nature of fourteenth century England. Ball, along with Wat Tyler, was one of the principal leaders of the Peasants’ Revolt – his sermon ends: "I exhort you to consider that now the time is come, appointed to us by God, in which ye may (if ye will) cast off the yoke of bondage, and recover liberty". The subsequent events of June 1381 represent a pivotal and thrilling moment in England’s history, characterised by murder and mayhem, beheadings and betrayal, a boy-King and his absent uncle, and a general riot of destruction and death. By most interpretations, the course of this sensational story threatened to undermine the very fabric of government as an awareness of deep injustice was awakened in the general populace.But who were the rebels and how close did they really come to upending the status quo? And just how exaggerated are claims that the Peasants’ Revolt laid the foundations of the long-standing English tradition of radical egalitarianism? With Miri Rubin, Professor of Early Modern History at Queen Mary, University of London; Caroline Barron, Professorial Research Fellow at Royal Holloway, University of London; Alastair Dunn, author of The Peasants’ Revolt - England’s Failed Revolution of 1381.

Pope

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the life and work of Alexander Pope. His enemies – who were numerous - described him as a hunchbacked toad, twisted in body, twisted in mind, but Alexander Pope is without doubt one of the greatest poets of the English language. His acerbic wit and biting satire were the scourge of politicians, fellow writers and most especially the critics. He was the first Englishman to make a living from his pen, free from the shackles of patronage and flattery. Indeed, his sharp tongue meant he couldn’t go out walking without his Great Dane and a pair of loaded pistols. He was a ferocious businessman too, striking tough deals with his publishers, ensuring he kept control of his work and was well-rewarded for it. So how did Pope manage to transform himself from a crippled outsider into a major cultural and moral authority? How did he shape our ideas about what a “modern author” is? Does his work still have resonances today or is it too firmly embedded in the politics, cultural life and rivalries of the period?With John Mullan, Professor of English at University College London; Jim McLaverty, Professor of English at Keele University; Valerie Rumbold, Reader in English Literature at Birmingham University.

The Poincaré Conjecture

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Poincaré Conjecture. The great French mathematician Henri Poincaré declared: “The scientist does not study mathematics because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful. If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing and life would not be worth living. And it is because simplicity, because grandeur, is beautiful that we preferably seek simple facts, sublime facts, and that we delight now to follow the majestic course of the stars.” Poincaré’s ground-breaking work in the 19th and early 20th century has indeed led us to the stars and the consideration of the shape of the universe itself. He is known as the father of topology – the study of the properties of shapes and how they can be deformed. His famous Conjecture in this field has been causing mathematicians sleepless nights ever since. He is also credited as the Father of Chaos Theory.So how did this great polymath change the way we understand the world and indeed the universe? Why did his conjecture remain unproved for almost a century? And has it finally been cracked?With June Barrow-Green, Lecturer in the History of Mathematics at the Open University; Ian Stewart, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick; Marcus du Sautoy, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford.

The Encyclopédie

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the French encyclopédie, the European Enlightenment in book form. One of its editors, D’Alembert, described its mission as giving an overview of knowledge, as if gazing down on a vast labyrinth of all the branches of human ideas, observing where they separate or unite and even catching sight of the secret routes between them. It was a project that attracted some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment - Voltaire, Rousseau and Diderot - striving to bring together all that was known of the world in one comprehensive encyclopaedia. No subject was too great or too small, so while Voltaire wrote of “fantasie” and “elegance”, Diderot rolled up his sleeves and got to grips with jam-making.The resulting Encyclopédie was a bestseller - running to 28 volumes over more than 20 years, amidst censorship, bans, betrayals and reprieves. It even got them excited on this side of the Channel, with subscribers including Oliver Goldsmith, Samuel Johnson and Charles Burney. So what drove these men to such lengths that they were prepared to risk ridicule, prison, even exile? How did the Encyclopédie embody the values of the Enlightenment? And what was its legacy – did it really fuel the French Revolution? With Judith Hawley, Senior Lecturer in English at Royal Holloway, University of London; Caroline Warman, Fellow and Tutor in French at Jesus College, Oxford; David Wootton, Anniversary Professor of History at the University of York.

The Needham Question

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Needham Question; why Europe and not China developed modern technology. What do these things have in common? Fireworks, wood-block printing, canal lock-gates, kites, the wheelbarrow, chain suspension bridges and the magnetic compass. The answer is that they were all invented in China, a country that, right through the Middle Ages, maintained a cultural and technological sophistication that made foreign dignitaries flock to its imperial courts for trade and favour. But then, around 1700, the flow of ingenuity began to dry up and even reverse as Europe bore the fruits of the scientific revolution back across the globe. Why did Modern Science develop in Europe when China seemed so much better placed to achieve it? This is called the Needham Question, after Joseph Needham, the 20th century British Sinologist who did more, perhaps, than anyone else to try and explain it.But did Joseph Needham give a satisfactory answer to the question that bears his name? Why did China’s early technological brilliance not lead to the development of modern science and how did momentous inventions like gunpowder and printing enter Chinese society with barely a ripple and yet revolutionise the warring states of Europe? With Chris Cullen, Director of the Needham Research Institute in Cambridge; Tim Barrett, Professor of East Asian History at SOAS; Frances Wood, Head of Chinese Collections at the British Library.

The Diet of Worms

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Diet of Worms, an event that helped trigger the European Reformation. Nestled on a bend of the River Rhine, in the South West corner of Germany, is the City of Worms. It’s one of the oldest cities in central Europe; it still has its early city walls, its 11th century Romanesque cathedral and a 500-year-old printing industry, but in its centre is a statue of the monk, heretic and founder of the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther. In 1521 Luther came to Worms to explain his attacks on the Catholic Church to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, and the gathered dignitaries of the German lands. What happened at that meeting, called the Diet of Worms, tore countries apart, set nation against nation, felled kings and plunged dynasties into suicidal bouts of infighting. But why did Martin Luther risk execution to go to the Diet, what was at stake for the big players of medieval Europe and how did events at the Diet of Worms irrevocably change the history of Europe? With Diarmaid MacCulloch, Professor of the History of the Church at Oxford University; David Bagchi, Lecturer in the History of Christian Thought at the University of Hull; Reverend Dr Charlotte Methuen, Lecturer in Reformation History at the University of Oxford.

Averroes

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the philosopher Averroes who worked to reconcile the theology of Islam with the rationality of Aristotle achieving fame and infamy in equal measure In The Divine Comedy Dante subjected all the sinners in Christendom to a series of grisly punishments, from being buried alive to being frozen in ice. The deeper you go the more brutal and bizarre the punishments get, but the uppermost level of Hell is populated not with the mildest of Christian sinners, but with non-Christian writers and philosophers. It was the highest compliment Dante could pay to pagan thinkers in a Christian cosmos and in Canto Four he names them all. Aristotle is there with Socrates and Plato, Galen, Zeno and Seneca, but Dante ends the list with neither a Greek nor a Roman but 'with him who made that commentary vast, Averroes'. Averroes was a 12th century Islamic scholar who devoted his life to defending philosophy against the precepts of faith. He was feted by Caliphs but also had his books burnt and suffered exile. Averroes is an intellectual titan, both in his own right and as a transmitter of ideas between ancient Greece and Modern Europe. His commentary on Aristotle was so influential that St Thomas Aquinas referred to him with profound respect as 'The Commentator'. But why did an Islamic philosopher achieve such esteem in the mind of a Christian Saint, how did Averroes seek to reconcile Greek philosophy with Islamic theology and can he really be said to have sown the seeds of the Renaissance in Europe? With Amira Bennison, Senior Lecturer in Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at the University of Cambridge; Peter Adamson, Reader in Philosophy at King's College London; Sir Anthony Kenny, philosopher and former Master of Balliol College, Oxford.

Humboldt

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander Von Humboldt. He was possibly the greatest and certainly one of the most famous scientists of the 19th century. Darwin described him as 'the greatest scientific traveller who ever lived'. Goethe declared that one learned more from an hour in his company than eight days of studying books and even Napoleon was reputed to be envious of his celebrity.A friend of Goethe and an influence on Coleridge and Shelly, when Darwin went voyaging on the Beagle it was Humboldt's works he took for inspiration and guidance. At the time of his death in 1859, the year Darwin published On the Origin of Species, Humboldt was probably the most famous scientist in Europe. Add to this shipwrecks, homosexuality and Spanish American revolutionary politics and you have the ingredients for one of the more extraordinary lives lived in Europe (and elsewhere) in the 18th and 19th centuries. But what is Humboldt's true position in the history of science? How did he lose the fame and celebrity he once enjoyed and why is he now, perhaps, more important than he has ever been? With Jason Wilson, Professor of Latin American Literature at University College London, Patricia Fara, Affiliated Lecturer in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, Jim Secord, Professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge and Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project.

Comedy in Ancient Greek Theatre

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss comedy in Ancient Greek theatre including Aristophanes and Menander. In The Birds, written by Aristophanes, two Athenians seek a Utopian refuge from the madness of city life and found a city of birds located between Earth and Olympus. Unfortunately, the idealism of their perfect new City - christened (in 414 BC) 'Cloud Cuckoo Land' - becomes corrupted and its decline was portrayed by one man (the chorus) playing 24 different species of bird. In one of Aristophanes' other politically anthropomorphic plays, The Wasps, was devised as an attack on the failures of Athenian democracy. It featured a chorus of actors dressed in black and yellow stripes who swarmed the stage stinging each other. Crammed with absurd images and satirical barbs, Comic theatre was a popular art form where mass appeal and coarse humour was combined with men in drag lambasting political figures and local big wigs. And from the fifth century BC onwards, Greek comic theatre fizzed and flourished, crossing boundaries of time and space, often informed by a savage political spleen. But how did Greek comedy evolve? Why did its subsequent development differ so radically from that of Greek tragedy? To what extent did it reflect the anxieties and preoccupations of a nascent democracy? And can it be said to have left any lasting legacy? With Paul Cartledge, Professor of Greek History at the University of Cambridge; Edith Hall, Professor of Drama and Classics at Royal Holloway, University of London; Nick Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Classics at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Pastoral Literature

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss pastoral literature.Come live with me and be my love, And we will all the pleasures prove That valleys, groves, hills, and fields, Woods or steepy mountain yields.And we will sit upon the rocks, Seeing the shepherds feed their flocks, By shallow rivers to whose falls Melodious birds sing madrigals. An entreaty from Christopher Marlowe's Passionate Shepherd to His Love - thought by many to be the crowning example of Elizabethan pastoral poetry. The traditions of pastoral poetry, literature and drama can be traced back to the third century BC and have principally offered a conventionalised picture of rural life, the naturalness and innocence of which is seen to contrast favourably with the corruption and artificialities of city and court life. Pastoral literature deals with tensions between nature and art, the real and the ideal, the actual and the mythical, and although pastoral works have been written from the point of view of shepherds or rustics, they have often been penned by highly sophisticated, urban poets and playwrights. But to what extent does pastoral literature represent a continuous yearning for a non-existent Golden Age of Innocence? How far did it evolve to reflect the social and political preoccupations of its times and what were the real meanings of its much used metaphors of town and country? With Helen Cooper, Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English at the University of Cambridge; Laurence Lerner, former Professor of English at the University of Sussex; Julie Sanders, Professor of English Literature and Drama at the University of Nottingham.

Galaxies

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the galaxies. Spread out across the voids of space like spun sugar, but harbouring in their centres super-massive black holes. Our galaxy is about 100,000 light years across, is shaped like a fried egg and we travel inside it at approximately 220 kilometres per second. The nearest one to us is much smaller and is nicknamed the Sagittarius Dwarf. But the one down the road, called Andromeda, is just as large as ours and, in 10 billion years, we'll probably crash into it. Galaxies - the vast islands in space of staggering beauty and even more staggering dimension. But galaxies are not simply there to adorn the universe; they house much of its visible matter and maintain the stars in a constant cycle of creation and destruction. But why do galaxies exist, how have they evolved and what lies at the centre of a galaxy to make the stars dance round it at such colossal speeds? With John Gribbin, Visiting Fellow in Astronomy at the University of Sussex; Carolin Crawford, Royal Society University Research Fellow at the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge; Robert Kennicutt, Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at the University of Cambridge.

The Spanish Inquisition

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Spanish Inquisition, the defenders of medieval orthodoxy. The word ‘Inquisition’ has its roots in the Latin word 'inquisito' which means inquiry. The Romans used the inquisitorial process as a form of legal procedure employed in the search for evidence. Once Rome's religion changed to Christianity under Constantine, it retained the inquisitorial trial method but also developed brutal means of dealing with heretics who went against the doctrines of the new religion. Efforts to suppress religious freedom were initially ad hoc until the establishment of an Office of Inquisition in the Middle Ages, founded in response to the growing Catharist heresy in South West France. The Spanish Inquisition set up in 1478 surpassed all Inquisitorial activity that had preceded it in terms of its reach and length. For 350 years under Papal Decree, Jews, then Muslims and Protestants were put through the Inquisitional Court and condemned to torture, imprisonment, exile and death. How did the early origins of the Inquisition in Medieval Europe spread to Spain? What were the motivations behind the systematic persecution of Jews, Muslims and Protestants? And what finally brought about an end to the Spanish Inquisition 350 years after it had first been decreed? With John Edwards, Research Fellow in Spanish at the University of Oxford; Alexander Murray, Emeritus Fellow in History at University College, Oxford;Michael Alpert, Emeritus Professor in Modern and Contemporary History of Spain at the University of Westminster