Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the ideas, people and events that have shaped our world.

Similar Podcasts

Crímenes. El musical

En la prensa de la España del XIX, los crímenes fueron un hit. Les gustaban tanto como hoy nos gusta el True Crime. A la vez fue asentándose la ciencia forense. En esta serie relatamos algunos de los crímenes más famosos de entonces, con mucha música y algunos coros. Y entrevistamos a una criminóloga y a científicos forenses de varias disciplinas: medicina, psicología, antropología, lingüística, biología...Suscríbete a nuestra newsletter y déjanos una propinilla aquí

Internet History Podcast

A History of the Internet Era from Netscape to the iPad Hosted on Acast. See acast.com/privacy for more information.

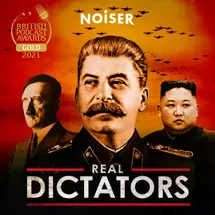

Real Dictators

Real Dictators is the award-winning podcast that explores the hidden lives of history's tyrants. Hosted by Paul McGann, with contributions from eyewitnesses and expert historians.

New episodes available a week early for Noiser+ subscribers. You'll also get ad-free listening, early access and exclusive content on shows across the Noiser podcast network. Click the subscription banner at the top of the feed to get started or head to noiser.com/subscriptions

For advertising enquiries, email info@adelicious.fm

Madame Bovary

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the literary sensation caused by Gustave Flaubert's novel Madame Bovary. In January 1857 a man called Ernest Pinard stood up in a crowded courtroom and declared, “Art that observes no rule is no longer art; it is like a woman who disrobes completely. To impose the one rule of public decency on art is not to subjugate it but to honour it”. Pinard was no grumbling hack, he was the imperial prosecutor of France, and facing him across the courtroom was the writer Gustave Flaubert. Flaubert’s work had been declared “an affront to decent comportment and religious morality”. It was a novel called Madame Bovary.The story of an adulterous housewife called Emma, Madame Bovary, is a vital staging post in the development of realism. The arguments in court involved a heady brew of art, morality, sex and marriage and ensured the fame of the novel and its author. With Andy Martin, Lecturer in French at the University of Cambridge; Mary Orr, Professor of French at the University of Southampton; Robert Gildea, Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford

The Pilgrim Fathers

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Pilgrim Fathers and their 1620 voyage to the New World on the Mayflower. Every year on the fourth Thursday in November, Americans go home to their families and sit down to a meal. It’s called Thanksgiving and it echoes a meal that took place nearly 400 years ago, when a group of religious exiles from Lincolnshire sat down, after a brutal winter, to celebrate their first harvest in the New World. They celebrated it in company with the American Indians who had helped them to survive.These settlers are called the Pilgrim Fathers. They were not the first and certainly not the largest of the early settlements but their Plymouth colony has retained a hold on the American imagination which the larger, older, violent and money-driven settlement of Jamestown has not.With Kathleen Burk, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at University College London; Harry Bennett, Reader in History and Head of Humanities at the University of Plymouth; Tim Lockley, Associate Professor of History at the University of Warwick

The Permian-Triassic Boundary

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Permian-Triassic boundary. 250 million years ago, in the Permian period of geological time, the most ferocious predators on earth were the Gorgonopsians. Up to ten feet in length, they had dog-like heads and huge sabre-like teeth. Mammals in appearance, their eyes were set in the side of their heads like reptiles. They looked like a cross between a lion and giant monitor lizard and were so ugly that they are named after the gorgons from Greek mythology – creatures that turned everything that saw them to stone. Fortunately, you’ll never meet a gorgonopsian or any of their descendants because they went extinct at the end of the Permian period. And they weren’t alone. Up to 95% of all life died with them. It’s the greatest mass extinction the world has ever known and it marks what is called the Permian-Triassic boundary. But what caused this catastrophic juncture in life, what evidence do we have for what happened and what do events like this tell us about the pattern and process of evolution itself?With Richard Corfield, Senior Lecturer in Earth Sciences at the Open University; Mike Benton, Professor of Vertebrate Palaeontology in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol; Jane Francis, Professor of Palaeoclimatology at the University of Leeds

Common Sense Philosophy

Melvyn Bragg looks at an unexpected philosophical subject - the philosophy of common sense. In the first century BC the Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero claimed “There is no statement so absurd that no philosopher will make it”. Indeed, in the history of Western thought, philosophers have rarely been credited with having much common sense. In the 17th century Francis Bacon made a similar point when he wrote “Philosophers make imaginary laws for imaginary commonwealths, and their discourses are as the stars, which give little light because they are so high”. Samuel Johnson picked up the theme with characteristic pugnacity in 1751 declaring that “the public would suffer less present inconvenience from the banishment of philosophers than from the extinction of any common trade.” Philosophers, it seems, are as distinct from the common man as philosophy is from common sense.But as Samuel Johnson scribbled his pithy knockdown in the Rambler magazine, the greatest philosophers in Britain were locked in a dispute about the very thing he denied them: Common Sense. It was a dispute about the nature of knowledge and the individuality of man, from which we derive the idea of common sense today. The chief antagonists were a minister of the Scottish Church, Thomas Reid, and the bon-viveur darling of the Edinburg chattering classes, David Hume. It's a journey that also takes in Rene Descartes, Immanuel Kant, John Locke and some of the most profound questions about human knowledge we are capable of asking.With A C Grayling, Professor of Philosophy at Birkbeck, University of London; Melissa Lane, Senior University Lecturer in History at Cambridge University; Alexander Broadie, Professor of Logic and Rhetoric at the University of Glasgow.

Renaissance Astrology

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss Renaissance Astrology. In Act I Scene II of King Lear, the ne’er do well Edmund steps forward and rails at the weakness and cynicism of his fellow men:This is the excellent foppery of the world, that,when we are sick in fortune, - often the surfeitof our own behaviour, - we make guilty of ourdisasters the sun, the moon, and the stars: asif we were villains by necessity.The focus of his attack is astrology and the credulity of those who fall for its charms. But the idea that earthly life was ordained in the heavens was essential to the Renaissance understanding of the world. The movements of the heavens influenced many things from the practice of medicine to major political decisions. Every renaissance court had its astrologer including Elizabeth Ist and the mysterious Dr. John Dee who chose the most propitious date for her coronation. But astrologers also worked in the universities and on the streets, reading horoscopes, predicting crop failures and rivalling priests and doctors as pillars of the local community. But why did astrological ideas flourish in the period, how did astrologers interpret and influence the course of events and what new ideas eventually brought the astrological edifice tumbling down? With Peter Forshaw, Lecturer in Renaissance Philosophies at Birkbeck, University of London; Lauren Kassell, Lecturer in the History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge; and Jonathan Sawday, Professor of English Studies at the University of Strathclyde.

Siegfried Sassoon

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the war poet Siegfried Sassoon. In 1916 the Military Cross was awarded to a captain in the Royal Welch Fusiliers for "conspicuous gallantry during a raid on the enemy's trenches". The citation noted that he had braved "rifle and bomb fire" and that "owing to his courage and determination, all the killed and wounded were brought in". The hero in question was the poet, Siegfried Sassoon. And yet a year later, and at great personal risk, Sassoon publicly denounced the conduct of the war in which he had fought so well.Although famous for his bitter, satirical verses and his denunciation of the conduct of the war which landed him in Craiglockhart mental hospital there is much more to this man of contradictions. A mentor to Wilfred Owen, arch enemy of T.S. Eliot and the Modernist movement, his life included a string of homosexual affairs, a failed marriage, a religious conversion and several tumultuous arguments with literary friends. Notably Robert Graves. He was also an obsessive diarist and writer of autobiography and he continued to write poetry until his death, from cancer, in 1967. But how significant a poet is Siegfried Sassoon, what version of Englishness did this half-Jewish, homosexual cricket lover invent for himself and how do you explain the mind of a man who bitterly opposed the First World War, yet fought in it with an almost insane ferocity?With Jean Moorcroft Wilson, Lecturer in English at Birkbeck, University of London and a biographer of Sassoon; Fran Brearton, Reader in English and Assistant Director of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry at the University of Belfast; Max Egremont, a biographer of Siegfried Sassoon

Ockham's Razor

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the philosophical ideas of William Ockham including Ockham's Razor. In the small village of Ockham, near Woking in Surrey, stands a church. Made of grey stone, it has a pitched roof and an unassuming church tower but parts of it date back to the 13th century. This means they would have been standing when the village witnessed the birth of one of the greatest philosophers in Medieval Europe. His name was William and he became known as William of Ockham.William of Ockham’s ideas on human freedom and the nature of reality influenced Thomas Hobbes and helped fuel the Reformation. During a turbulent career he managed to offend the Chancellor of Oxford University, disagree with his own ecclesiastical order and get excommunicated by the Pope. He also declared that the authority of rulers derives from the people they govern and was one of the first people so to do. Ockham’s razor is the idea that philosophical arguments should be kept as simple as possible, something that Ockham himself practised severely on the theories of his predecessors. But why is William of Ockham significant in the history of philosophy, how did his turbulent life fit within the political dramas of his time and to what extent do we see his ideas in the work of later thinkers such as Thomas Hobbes and even Martin Luther?With Sir Anthony Kenny, philosopher and former Master of Balliol College, Oxford; Marilyn Adams, Regius Professor of Divinity at Oxford University; Richard Cross, Professor of Medieval Theology at Oriel College, Oxford

The Siege of Orléans

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Siege of Orléans, when Joan of Arc came to the rescue of France and routed the English army with the help of God. The perfidious English then burnt her as a heretic in Rouen marketplace. At least that's the story we're told but the truth involves the murky world of French court politics, labyrinthine dynastic claims, mass religious hysteria and English military and political incompetenceLooking back on the events that followed, the Duke of Bedford wrote to King Henry VI and declared “all things prospered for you till the time of the siege of Orleans, taken in hand God knoweth by what advice”.But what happened at the siege of Orleans, did Joan of Arc really rescue the city and how significant was the battle in changing the course of the 100 Years' War and the subsequent histories of England and France?With Anne Curry, Professor of Medieval History at the University of Southampton; Malcolm Vale, Fellow and Tutor in History at St John’s College, Oxford; Matthew Bennett, Senior Lecturer at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst.

Gravitational Waves

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss mysterious phenomena called Gravitational Waves in contemporary physics. The rather un-poetically named star SN 2006gy is roughly 150 times the size of our sun. Last week it went supernova, creating the brightest stellar explosion ever recorded. But among the vast swathes of dust, gas and visible matter ejected into space, perhaps the most significant consequences were invisible – emanating out from the star like the ripples from a pebble thrown into a pond. They are called Gravitational Waves, predicted by Einstein and much discussed since, their existence has never actually been proved but now scientists may be on the verge of measuring them directly. To do so would give us a whole new way of seeing the cosmos. But what are gravitational waves, why are scientists trying to measure them and, if they succeed, what would a gravitational picture of the universe look like?With Jim Al-Khalili, Professor of Physics at the University of Surrey; Carolin Crawford, Royal Society Research Fellow at the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge; Sheila Rowan, Professor in Experimental Physics in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Glasgow

Victorian Pessimism

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss Victorian Pessimism. On 1 September 1851 the poet Matthew Arnold was on his honeymoon. Catching a ferry from Dover to Calais, he sat down and worked on a poem that would become emblematic of the fears and anxieties of a generation of Victorians. It is called Dover Beach and it finishes like this: “Ah, love, let us be true To one another! for the world, which seemsTo lie before us like a land of dreams,So various, so beautiful, so new,Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;And we are here as on a darkling plainSwept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,Where ignorant armies clash by night”.From Matthew Arnold’s poem Dover Beach to the malign universe of Thomas Hardy’s novels, an age famed for its forthright sense of progress and Christian belief was also riddled with anxieties about faith, morality and the future of the human race. They were even worried that the sun would soon go out. But to what extent was this pessimism spread across all areas of Victorian life? What events and ideas were driving it on and were any of their concerns about race, religion, class and culture borne out as the 19th century drew to a close? With Dinah Birch, Professor of English at the University of Liverpool; Rosemary Ashton, Quain Professor of English Language and Literature at University College London; Peter Mandler, University Lecturer and Fellow in History at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge.

Spinoza

Melvyn Bragg discusses the Dutch Jewish Philosopher Spinoza. For the radical thinkers of the Enlightenment, he was the first man to have lived and died as a true atheist. For others, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, he provides perhaps the most profound conception of God to be found in Western philosophy. He was bold enough to defy the thinking of his time, yet too modest to accept the fame of public office and he died, along with Socrates and Seneca, one of the three great deaths in philosophy. Baruch Spinoza can claim influence on both the Enlightenment thinkers of the 18th century and great minds of the 19th, notably Hegel, and his ideas were so radical that they could only be fully published after his death. But what were the ideas that caused such controversy in Spinoza’s lifetime, how did they influence the generations after, and can Spinoza really be seen as the first philosopher of the rational Enlightenment?With Jonathan Rée, historian and philosopher and Visiting Professor at Roehampton University; Sarah Hutton, Professor of English at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth; John Cottingham, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Reading.

Greek and Roman Love Poetry

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss Greek and Roman love poetry, from the Greek poet Sappho and her erotic descriptions of romance on Lesbos, to the love-hate poems of the Roman writer Catullus. The source of many of the images and metaphors of love that have survived in literature through the centuries. We begin with the words of Sappho, known as the Tenth Muse and one of the great love poets of Ancient Greece: “Love, bittersweet and inescapable, creeps up on me and grabs me once again”Such heartfelt imploring by Sappho and other writers led poetry away from the great epics of Homer and towards a very personal expression of emotion. These outpourings would have been sung at intimate gatherings, accompanied by the lyre and plenty of wine. The style fell out of fashion only to be revived first in Alexandria in the third Century BC and again by the Roman poets starting in the 50s BC. Catullus and his peers developed the form, employing powerful metaphors of war and slavery to express their devotion to their Beloved – as well as the ill treatment they invariably received at her hands!So why did Greek poetry move away from heroic narratives and turn to love in the 6th Century BC? How did the Romans transform the genre? And what effect did the sexual politics of the day have on the form? With Nick Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Classics at Royal Holloway, University of London; Edith Hall, Professor of Classics and Drama at Royal Holloway, University of London; Maria Wyke, Professor of Latin at University College London.

Symmetry

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss symmetry. Found in Nature - from snowflakes to butterflies - and in art in the music of Bach and the poems of Pushkin, symmetry is both aesthetically pleasing and an essential tool to understanding our physical world. The Greek philosopher Aristotle described symmetry as one of the greatest forms of beauty to be found in the mathematical sciences, while the French poet Paul Valery went further, declaring; “The universe is built on a plan, the profound symmetry of which is somehow present in the inner structure of our intellect”.The story of symmetry tracks an extraordinary shift from its role as an aesthetic model - found in the tiles in the Alhambra and Bach's compositions - to becoming a key tool to understanding how the physical world works. It provides a major breakthrough in mathematics with the development of group theory in the 19th century. And it is the unexpected breakdown of symmetry at sub-atomic level that is so tantalising for contemporary quantum physicists.So why is symmetry so prevalent and appealing in both art and nature? How does symmetry enable us to grapple with monstrous numbers? And how might symmetry contribute to the elusive Theory of Everything?With Fay Dowker, Reader in Theoretical Physics at Imperial College, London; Marcus du Sautoy, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Oxford; Ian Stewart, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick.

The Opium Wars

Melvyn Bragg discusses the Opium Wars, a series of conflicts in the 19th Century which had a profound effect on British Chinese relations for generations. Thomas De Quincey describes the pleasures of opium like this: “Thou hast the keys of Paradise, O just, subtle and mighty opium”. The Chinese had banned opium in its various forms several times, citing concern for public morals, but private British traders continued to smuggle large quantities of opium into China from India. In this way, the opium trade became a way of balancing a trade deficit brought about by Britain's own addiction...to Indian tea.The Chinese protested against the flouting of the ban, even writing to Queen Victoria. But the British continued to trade, leading to a crackdown by Lin Tse-Hsu, a man appointed to be China's Opium Drugs Czar. He confiscated opium from the British traders and destroyed it. The British military response was severe, leading to the Nanking Treaty which opened up several of China's ports to foreign trade and gave Britain Hong Kong. The peace didn't last long and a Second Opium War followed. The Chinese fared little better in this conflict, which ended with another humiliating treaty.So what were the main causes of the Opium Wars? What were the consequences for the Qing dynasty? And how did the punitive treaties affect future relations with Britain?With Yangwen Zheng, Lecturer in Modern Chinese History at the University of Manchester; Lars Laamann, Research Fellow in Chinese History at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London; Xun Zhou, Research Fellow in History at SOAS, University of London

St Hilda

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the 7th century saint, Hilda, or Hild as she would have been known then, wielded great religious and political influence in a volatile era. The monasteries she led in the north of England were known for their literacy and learning and produced great future leaders, including 5 bishops. The remains of a later abbey still stand in Whitby on the site of the powerful monastery she headed there. We gain most of our knowledge of Hilda's life from The Venerable Bede who wrote that she was 66 years in the world, living 33 years in the secular life and 33 dedicated to God. She was baptised alongside the king of Northumbria and with her royal connections, she was a formidable character. Bede writes: “Her prudence was so great that not only indifferent persons but even kings and princes asked and received her advice”. Hild and her Abbey at Whitby hosted the Synod which decided when Easter would be celebrated, following a dispute between different traditions. Her achievements are all the more impressive when we consider that Christianity was still in its infancy in Northumbria. So what contribution did she make to establishing Christianity in the north of England? How unusual was it for a woman to be such an important figure in the Church at the time? How did her double monastery of both men and women operate on a day-to-day basis? And how did she manage to convert a farmhand into England's first vernacular poet?With John Blair, Fellow in History at The Queen's College, Oxford; Rosemary Cramp, Emeritus Professor in Archaeology at Durham University; Sarah Foot, Professor of Early Medieval History at Sheffield University.